There’s so much pressure for undergrad computer science students to land an internship.

So there’s a lot of advice on how to get them.

Optimize your resume.

Get referrals.

Send out applications, play the numbers game, prepare for the coding interview, LeetCode, etc, etc, etc.

Useful stuff.

However, I think there’s a lack of resources on how to actually do well during these internships.

I’ve done a few, and each time after I get the job, a sudden pang of anxiety hits me before the summer: landing the job isn’t enough - I actually have to perform well on the job!

Here are some insights I’ve learned that I found to be somewhat unintuitive, or maybe even uncomfortable, but could help you perform a little better at a software engineering internship.

Ok, I take that back. Maybe it’s completely intuitive to you, but at least it wasn’t for me a few years ago.

Whatever… Just read on if you like.

Communication

-

Clearly communicate about how you’re going to communicate.

Meta, right?

Ask if your manager prefers Slack vs Email vs whatever internal chat system your company’s got.

Ask your manager what time he/she is typically online and open to pings.

-

Setup a regular check-in time with your direct manager.

Two summers ago I did weekly check-ins. This summer I did daily syncs (<10 min) almost every day.

Especially due to COVID-19, these syncs were incredibly helpful in keeping a rhythm going and my manager in sync.

-

Advocate for yourself.

Do not rely on your managers to advocate on your behalf. Do it yourself.

This means go out of your way to broadcast your successes, and all of the impact that your project is having to the rest of your team.

If you feel bad self-advocating, think about it this way: you are taking the burden of advocating for you off of your manager.

Being humble, and waiting for your manager to do this is not respectable, it’s selfish.

-

Ask for feedback at least on a weekly basis.

Feedback is a gift.

It is the most helpful thing that both your peers and your manager can offer you.

Your midpoint and final feedback should not be a surprise to you. In fact, these final feedback reviews should be a bore, as it’s been the same things you’ve been hearing all summer long.

-

Show that you have thick skin.

Following closely after point 4, if you want honest feedback, you gotta be honest with your manager.

I think it’s easy to forget that managers can also have a hard time giving you feedback.

Most people are nice. They don’t like to hurt feelings.

So in order to get honest feedback, you have to convince them you have thick skin, and can have hard conversations (whether you can or cannot is a whole different concern).

If you feel like you could’ve done a better job on a task, then tell them “I don’t think I did x quite well enough. I recognize that and I’ll spend a few moments refactoring x, and I’ll avoid making the same mistake going forward”.

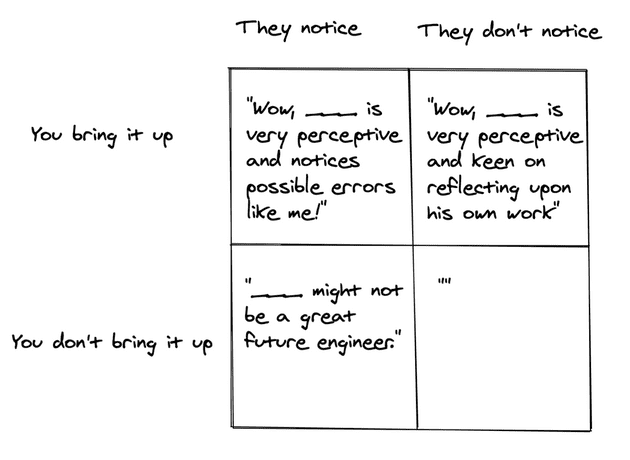

Consider the following possibilities:

I don’t think this diagram perfectly encapsulates this idea, but I think you get the point…

Basically, the downside of not bringing up potential problems with your work is much worse than the downside of bringing up a problem that they don’t notice.

Being transparent goes a long way.

Technical

-

Document heavily.

If you’re ever on the fence about whether you should add that extra comment in your code, or add extra detail in that commit message, air on the side of caution and add it.

This also goes for when you’re reading other people’s code.

If you’re tasked with something that involves understanding someone else’s confusing ass module, do everyone a favor, and document the parts that are confusing.

Write comments, add doc strings, contribute to that damn README.md file.

It ensures that you have a solid understanding, and that others won’t run into the same confusion later on.

-

Do the dirty work.

Companies will vary in their ability to setup systems that avoid tech debt, but it’s impossible to completely avoid.

Where there is software, there will be tech debt of some form, however small. Where there are systems, there will be inefficiencies.

To the extent that it does not compromise your ability to finish the main tasks you’ve been assigned, try to refactor shitty old code, squash those annoying bugs, clean up those logs, make that error handling sturdier.

Good engineers will always appreciate someone who pays attention to the little details, and will go out of their way to fix some small tech debt that’s been bugging them for a long time, but they haven’t found the time to tend to.

-

Know who your peers are, specifically the ones whose shoulders you’ll have to tap on for help.

These people might become your lifeline. If you get off on the wrong foot, it might be difficult for them to think of you as any more than a distraction.

On the other hand, if you fail to ask for crucial advice out of fear of being a distraction, you could be sabotaging yourself in the long run.

-

Take note of every task you do.

This will be especially important if you have self-evaluations. This helps you do 5 in communication.

Miscellaneous

-

Make friends!

You might become life-long friends with some of these people, especially other interns.

I’ve heard of stories of co-founders, or even partners meeting each other during internships.

-

Have fun!

Life is too short to toil away about your career in software. Enjoy the damn perks you worked so hard to get.

You’ll notice that most of the advice I’m offering is non-technical, about how to communicate.

And it’s for good reason.

Too often I see early career engineers (including myself) think that technical ability alone will bring all the career success in the world. If you ever have to work in a team, this could not be further from the truth.

As I get more experience, I’m becoming more and more convinced that technical ability is just a baseline requirement. It’s communication and coordination skills that take an engineer to the next level of competency.

But then again, I haven’t met many people with truly incredible technical chops.

Maybe I’m wrong. Maybe I’m just too inexperienced.